What's Happening?

Community conflict is not a game

The idea for a virtual reality police de-escalation training program came to Dane Jennings in what he  describes as a eureka moment.

describes as a eureka moment.

Deeply troubled by the death of George Floyd, the 27-year-old wondered how he might use his skills to help police officers navigate volatile situations without resorting to force.

Then, suddenly, it came to him: Why not use cutting-edge technology to train law enforcement officers to defuse conflict using non-violent de-escalation techniques?

“This was an idea that really just felt right to me,” said Jennings, CEO of Catapult Games, a Schenectady-based software development studio, who added he became consumed by the idea. “In no time at all, it was the only thing I could think of.”

What makes Jennings’ software unique is how it was developed: with input from the community.

The unusual approach attracted the interest of The Schenectady Foundation, which helped support the project.

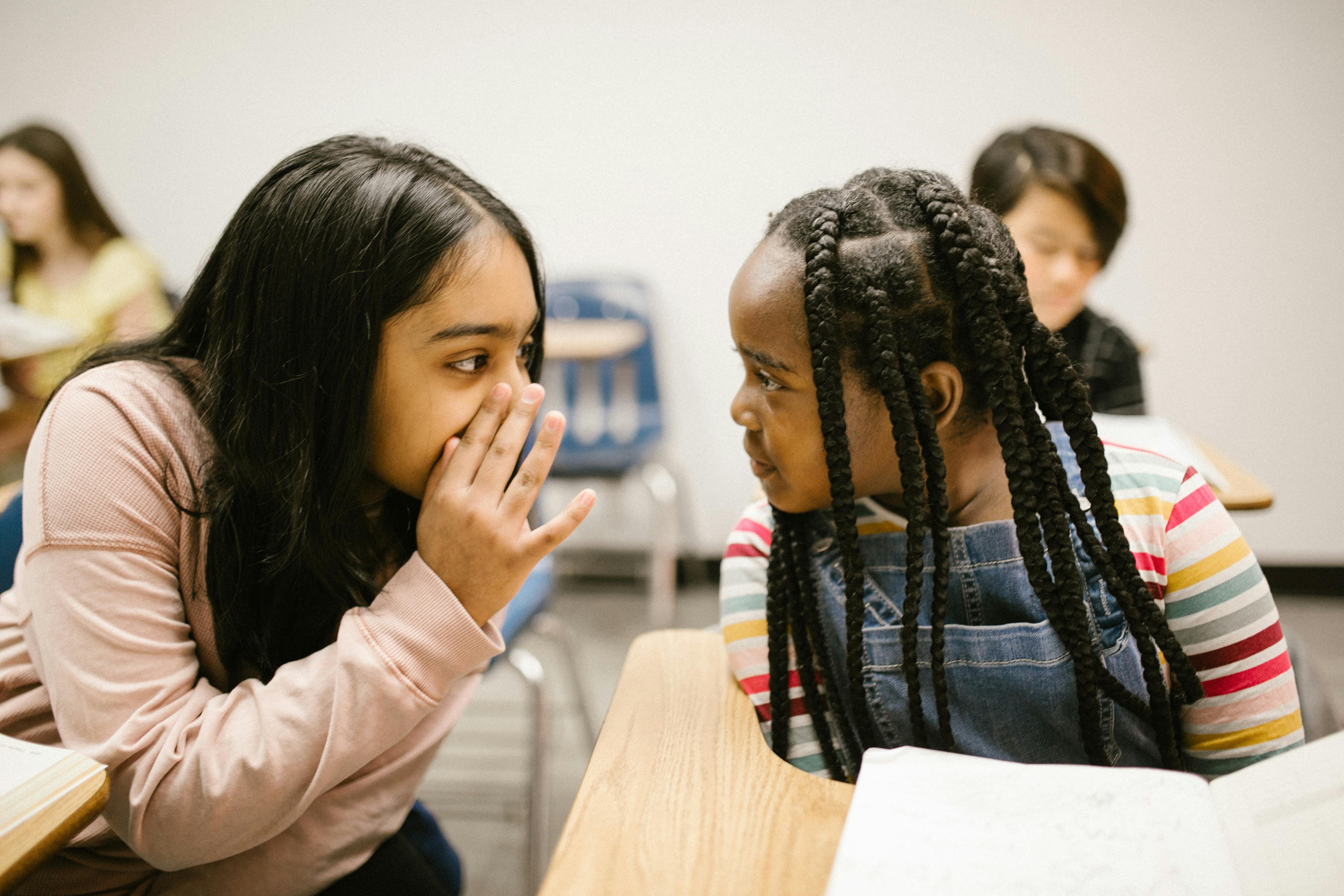

In March, Jennings presented his software - which remains a work in progress - to residents, community leaders and other interested stakeholders at the Boys & Girls Club’s Mont Pleasant headquarters.

It was the fifth community conversation focused on the software, with participants providing answers to wide-ranging and challenging questions such as “when you hear the word de-escalation, what comes to mind?” and “are there situations where use of force is warranted?”

It was the fifth community conversation focused on the software, with participants providing answers to wide-ranging and challenging questions such as “when you hear the word de-escalation, what comes to mind?” and “are there situations where use of force is warranted?”

Present at all discussions has been a Schenectady police officer, who listens and occasionally shares insights and perspective.

“For me, these community conversations are the most important thing about what we’re doing,” Jennings said. “This is how we bridge the gap between the police and the community and build trust.”

“The whole process has been absolutely amazing,” said Shawnta Rivas, a Schenectady resident who has attended all of the community conversations.

Initially, Rivas was skeptical.

But Jennings eventually won her over.

She could see that he was listening and responding to community concerns - “he always had a notebook, he was always taking notes” - and she appreciated how he and the discussion moderators created a “safe space” where residents and police could sit down and talk freely.

“It helps the community and the police to have a conversation with each other, to learn from each other,” Rivas said. “I would never before have thought to ask a police officer the questions I asked in that room.”

Here’s how the virtual reality police de-escalation training program works: The user puts a virtual reality headset on and plays the role of a police officer responding to an agitated subject holding a knife.

What the officer chooses to do can either escalate or de-escalate the situation, calming the subject or making him more agitated. The subject is controlled by a second user. The police officer’s goal: convincing the subject to put the knife down.

The feedback from the community conversations has resulted in major changes in the virtual reality police de-escalation training program, with Jennings working hard to make it more realistic for users.

“At first, the setting was a suburban waterfront-type setting,” Jennings recalled. “The feedback I got was ‘This isn’t realistic.’” The encounter now unfolds on an urban streetscape.

The project is collaborative in nature, with Jennings working closely with the local non-profit organization The Center for Community Justice, community activist William Rivas and Schenectady Police Chief Eric Clifford.

The Schenectady Foundation funding was split into two parts: $11,000 to CCJ for the resident engagement piece, and a maximum of $60,000 to Catapult Games.

The hope is that one day the program will be used by police departments and community members - in Schenectady and beyond.

Folks attending the fifth community conversation at the Boys and Girls Club in March.